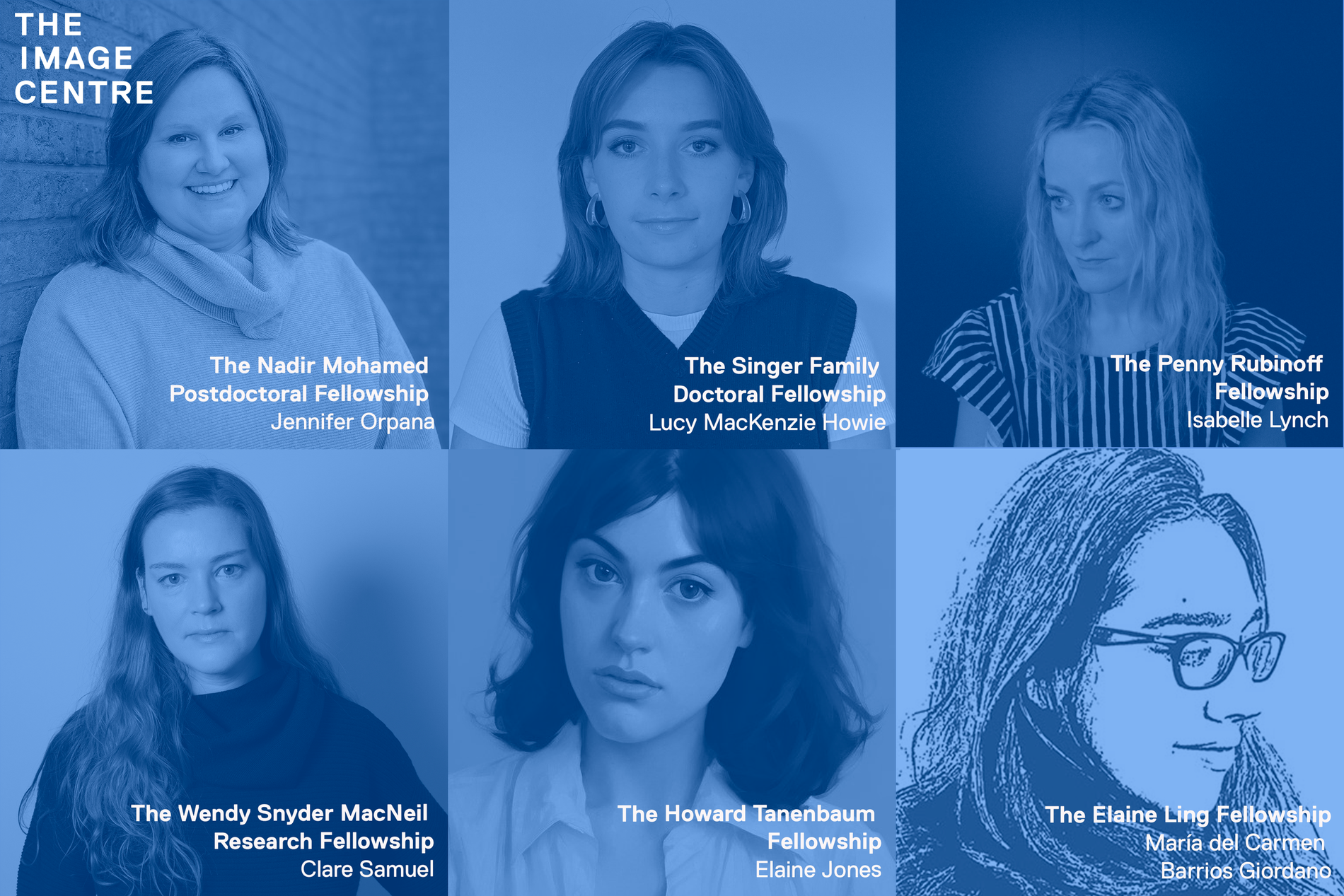

Clockwise L-R: 2024 IMC Research Fellows Jennifer Orpana, Lucy MacKenzie Howie, Isabelle Lynch, Clare Samuel, Elaine Jones, María del Carmen Barrios Giordano

Meet The Image Centre’s 2024 Photography Research Fellows

Jan. 18, 2024

Six new fellows will be welcomed into The Image Centre’s (IMC) Peter Higdon Research Centre this year to explore themes in the IMC’s photography collection, ranging from Victor de Palma’s legacy to t-shirts in the Civil Rights Movement. Read on to learn more about this year’s fellows.

The Nadir Mohamed Postdoctoral Fellowship

Jennifer Orpana | Examining the Proof: The Retouching Practices of Violet Keene Perinchief

Jennifer Orpana is a photography historian and lecturer, with experience teaching topics in photography and museum studies at Toronto Metropolitan University, University of Toronto, OCAD University, Western University, and Brock University. She has worked on education, community outreach, development, and curatorial teams at some of Canada’s leading arts and culture institutions, including the Art Gallery of Ontario, the National Ballet of Canada, and the Royal Ontario Museum. Her writing has been published in RACAR, Fuse Magazine, and Trans Asia Photography, and she coedited a Photography & Culture special issue on family photography with Sarah Parsons (2017).

Tell us about your project.

This project explores a box of negatives, proofs, handwritten notes, and envelopes from Violet Keene Perinchief’s Oakville studio, spanning from the late 1940s to the 1970s. Produced in the later years of Keene’s professional career, this part of the collection is highly instructive of several key aspects of her portrait studio practice. These documents are complex sites that reflect the personal desires of sitters, reveal the mainstream expectations related to female subjects and idealized feminine bodies, and illustrate how these ideals were further negotiated and articulated in post-production. The notes found on the envelopes and the messages tucked within them reveal the interactions between photographer and clientele, as well as information about order details and prices. On several envelopes, Keene’s handwriting captures her business practice, by indicating when follow-ups are needed, who to contact in the household, and which images could be used as samples. Additionally, many of the proofs, particularly of female subjects, have been marked in pen by the photographer to identify areas in need of retouching. These markings reveal suggested edits such as the cropping of hair styles, the flattening of wrinkles in clothing, the highlights needed on jewelry, or alterations to the subject’s body. The contents of this box reveal social and technical aspects of Keene’s practice in ways that help us to look beyond the visual codes in the final portraits and to see key moments that led to their production.

How would you describe your research interests and methods?

This project connects to my research interests in topics related to the practices and production of family photography and the history of mid-century studio photography in Canada. This work connects to a greater research project that I am undertaking that explores the life and work of Violet Keene Perinchief. The methodologies that I am using include carefully cataloguing the exchanges between the photographer and her subjects, the suggested edits sketched out on the proofs, and the administrative notes written by Keene in the Image Centre’s collection of her Oakville studio negatives. I also plan to use the time afforded by the fellowship to better my understanding of the processes by which negatives were retouched and how to better document these edits through research and consultation. Finally, I will consider how the retouching practices revealed by the archive fit into broader social and historical contexts and connect to existing scholarship on the histories of photography.

What initially drew you to your particular area of research?

I first encountered the photography of Violet Keene Perinchief while cataloguing a portrait of Elizabeth Jaco as a ROM Research Associate. This portrait is part of The Family Camera Network’s public archive of family photographs and oral histories. I was struck by her signature, which was energetically scrawled in pencil and assertively underlined at the lower, left-hand corner of the mat. Eager to learn more about this Toronto-based, mid-century female studio photographer, I sought her work in other local collections. I visited the City of Toronto Archives, where I examined more portraits and an exhibition pamphlet, and later conducted research at the Image Centre, where I had the pleasure of examining portraits from the extensive Minna Keene and Violet Keene Perinchief collection. I also conducted an extensive search for her studio ads and photographs in the Toronto dailies to learn more about her promotions, practice, and the public circulation of her works. I found that despite her prolific work and her undeniable presence as a studio photographer in Toronto from the 1930s to the 1970s, there is still much to be done to represent Violet Keene in the historical narratives on studio photography in Toronto, as well as the broader histories of Canadian photography.

The Singer Family Doctoral Fellowship

Lucy MacKenzie Howie | Disability, Sexuality and the Politics of Representation: A Reconsideration of Jo Spence's Photo Therapy in 1980s Britain

Lucy MacKenzie Howie is a SGSAH/AHRC PhD researcher at the University of St Andrews where her thesis focuses on lens-based media from the 1980s–1990s Britain exploring the representation of sexuality and health. She has worked as a Curatorial Assistant at Kettle's Yard, University of Cambridge, and writes regularly for the international art press. Lucy has programmed public events and film screenings at Kettle's Yard (UK), Cambridge Central Library (UK), Edinburgh College of Art (UK) and the University of St Andrews (UK) on projects spanning feminist collections, community art and aesthetics, and HIV/AIDS and disability.

Tell us about your project.

This project will use the Jo Spence Memorial Archive housed at The Image Centre to analyse the intersecting but often overlooked histories of disability, sexuality, and the politics of representation in photography in 1980s Britain. This will be explored through Jo Spence’s ‘photo therapy’ practice that formed a part of Spence’s critique of Western orthodox medicine and traditional therapies, bringing sexuality, class, and gender to the forefront of discussions on health. This research locates where Spence and her cultural network transformed debates in documentary photography and self-imaging practices to new ends in the context of disability rights activism and in response to Section 28 during this period. Photo therapy will be examined as a radical self-imaging technique that deconstructed pervasive categories of photography like the family album and commercial studio portraiture, which are inextricable from constructions of heteronormativity and ideals of the healthy body.

The Penny Rubinoff Fellowship

Isabelle Lynch | Artificial Light: Photography and Alternative Illumination c. 1860–1910

Isabelle Lynch is a PhD candidate in History of Art at the University of Pennsylvania where she studies modern and contemporary art with a focus on photography and film from the mid-nineteenth century to the present. Her dissertation investigates how the use of artificial light in processes of photographic exposure and development altered photography’s relationship to time, space, and the image. She has held positions in curatorial and education departments at the Art Institute of Chicago, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Institute of Contemporary Art Philadelphia, the Art Museum at the University of Toronto, and the National Gallery of Canada. She currently lives between Chicago and Paris, where she teaches at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and at Paris College of Art.

Tell us about your project.

My project interrogates how photography by artificial light sought to recast the limits of the visible world from the mid-nineteenth to the early twentieth century. While histories and theories of photography tend to take the sun’s light as a given—a freely available natural resource that illuminates everything equally everywhere—my dissertation argues that the discovery, invention, and extraction of new materials and technologies of illumination such as limelight, magnesium light, and electricity signaled an important shift from photography’s reliance on the light of the sun to photography’s engagement with materials dislodged from the earth’s crust or made by human hands as alternative sources of illumination. My project’s central premise is that the development and use of artificial light to expand the perimeters of human vision was enmeshed with greater ambitions to conquer time and space and manipulate the limits of what can be known.

How would you describe your research interests and methods?

Drawing together materials from an array of cultural practices including news media, scientific images, educational lantern slides, photographs, films, stereograph cards, and optical toys, my interdisciplinary inquiry proposes an expansive definition of photography that includes mass media, popular culture, and vernacular images to think about questions and developments across art and science. My project aims to intervene in current debates that foreground interactions between technical media and the environment to think about the material and environmental impact of media or the ways in which media are themselves connected to elements of the natural world. Situated at the intersection of Art History and Cinema and Media Studies, my dissertation advances scholarly research in the field of photography by bridging discussions occurring across disciplines—in the environmental humanities, in cinema and media studies, and in art history—to pose timely questions about photography’s relationship to industry, environment, and scientific pursuits.

What initially drew you to your particular area of research?

While studying histories and theories of photography, it struck me that most writings on photography tend to take the sun’s totalizing light as a given: a freely available natural resource that illuminates everything equally everywhere. While conducting research in nineteenth-century photography journals and technical manuals, I became fascinated with advertisements and articles that promote, praise, and explain the use of various forms of artificial light that could be used in photographic practices as various developments in art and science led to the use of artificial light in photography as early as 1839.

Choose a work from the IMC collections and explain its significance to your research.

Charles Bierstadt, Crystal Grotto, c. 1889. Through a diverse range of objects including stereographs, lantern slides, and early films, my project's first chapter considers the role of artificial light in photographs of mines, tombs, caves, and catacombs. I explore how artificial light stereograph cards of subterranean spaces reveal significant points of connection between the practice of lighting and photographing underground networks and contemporary notions of western expansion. It is likely that Bierstadt made use of magnesium light to photograph the Crystal Grotto at Niagara Falls during the last decade of the nineteenth century.

The Howard Tanenbaum Fellowship

Elaine Jones | The Civil Rights Movement Through T-Shirts

Elaine Jones (she/her) is a graduate student in the Photography Preservation and Collections Management program at Toronto Metropolitan University. She holds a Bachelor of Arts in History, with a Minor in Curatorial Studies from TMU and a Masters in History from the University of Waterloo.

Tell us about your project.

For decades, printed T-shirts have been used as a means to convey messaging from the wearer to the world. In 2021, I published Politics Through T-Shirts: A History of Protest, an exploration of the origins of the T-shirt and its adoption by American protest movements. The online exhibition is free to view at www.tshirtsandprotest.com. Through this fellowship at The Image Centre, I will continue my previous work applying the lens to the Civil Rights Movement. By utilizing the Black Star Collection, I intend to examine the importance placed on the use of the printed T-shirt by Civil Rights activists as a means of furthering the message of equal rights.

How would you describe your research interests and methods?

My research interests are predominantly modern US and Canadian history since 1945, exploring the symbiotic nature of clothing and social/political histories. I’m also interested in the history of popular culture and its underlying social or political context, and always seeking to find the connections in human experiences and how they are relevant in a contemporary context.

What initially drew you to your particular area of research?

I've always been curious about the world around me and how it came to be. The study of history and the language of clothing has always spoken to me in that people have always projected personal beliefs and attitudes through styles of dress, whether it was a conscious choice or not. By tracking these choices throughout history and aligning them with the predominant social and political movements of the era, we gain a sense of how the world has evolved into its current state.

The Elaine Ling Fellowship

María del Carmen Barrios Giordano | Victor de Palma in Mexico: Fotoprensa and Black Star

María del Carmen Barrios Giordano is a graduate student at the UNAM (the National Autonomous University of Mexico) in art history. She has a special interest in the history of photography across the Americas. Giordano received a bachelor's degree from Stanford University where she studied history of science and international relations, and then went on to lead a dilettantish existence between museum education, publishing, and sewing.

Tell us about your project.

Victor de Palma was an American photojournalist who in the late 1940s and 1950s called Mexico City home. During his time in Mexico, De Palma set up TV and radio stations, ran a photo lab and studio, mentored youth, and sparked the career of perhaps the most revered Mexican photojournalist of the 20th-century: Nacho López. Regrettably, his influence on the history of photography in Mexico is lost; he is neither mentioned nor cited in any scholarly research about Mexican photography, his name is unheard of among photography specialists, and his work has never been exhibited in the country. "Victor de Palma in Mexico" fills this gap, exploring how this expat photojournalist in the 1940s and 50s fit into the vibrant world of mid-century Mexican fotoprensa (photo press).

How would you describe your research interests and methods?

I am interested in demonstrating how some historical narratives ossify where others fail to materialize: that is, I believe history is continuously constructed, and that this activity is a human trait. I care about intellectual rigor and like to take my time with ideas. The work of Alessandro Portelli, Ruth Schwartz Cowan, Patrick Maynard and Miguel León Portilla is dear to me and shapes my thought; the self-awareness of oral history and the social constructivist theory of the history of technology are important touchstones. I aspire to write about photography in as lucid a manner as Charlotte Cotton and Olivia Laing.

What initially drew you to your particular area of research?

Curiosity: I had a question for which I could not find an answer. That question mushroomed into several and now here we are. I like detective work, and photographs are deliciously suited to that kind of pursuit.

How has your research changed over time?

I've flirted with perhaps all the possible history subfields, except military history, and now find myself drawn to the most traditional method of them all: biography! I did not expect this ten years ago, and surmise it has something to do with the ineluctable draw that storytelling has on my brain, as individual lives do seem so much better suited for telling stories.

Choose a work from the IMC collections and explain its significance to your research.

There's a portrait by Victor de Palma of Diego Rivera next to the colossal Olmec head called Monumento 1, at La Venta, Tabasco, that was likely taken while Carlos Pellicer, a Mexican intellectual, was trying to get government support for the site, threatened by oil drilling nearby. Pellicer eventually succeeded, but his heavy-handed intervention caused serious losses of archaeological data. It's a fascinating example of how, in mid-century, the Mexican state—through its cultural operators—was intent on constructing a national identity based on highly suspect interpretations of the pre-Hispanic past, and De Palma, an American, was there to document it. I hope to find other photographs from this reportage so I may identify its precise date and context.

What is the goal of your research?

I am trying to resuscitate someone. Once the name Victor de Palma is listed in ULAN or some other authority record, I'll be content.

The Wendy Snyder MacNeil Research Fellowship

Clare Samuel | An Artistic Dialogue with Wendy Snyder MacNeil

Clare Samuel is a visual artist originally from Northern Ireland, now living as a settler in Tkaronto. She holds a BFA from Toronto Metropolitan University and an MFA from Concordia University. Her work focuses on connection and distances between the self and other, as well as notions of social division, borders, and belonging. Spanning mediums such as photography, video, text and installation, her projects are often a dialogue with the idea of portraiture. She has exhibited internationally, most recently at OBORO, Belfast Exposed and VU Photo. She teaches at OCADU, Toronto Metropolitan University, and University of Toronto. Her practice has been supported by Canada Council for the Arts, Ontario Arts Council and Toronto Arts Council. Clare is co-founder and co-director of Feminist Photography Network, a nexus for research on the relationship between feminism and lens-based media.

Tell us about your project.

My intention is to have an in-depth dialogue with Wendy Snyder MacNeil's work in expanded forms of portraiture. As a mid-career and middle-aged artist whose focus has been the representations of individuals and groups, I’m entering a period of reflection and change in my practice. This conversation with the archive, the life and legacy, of a pioneering female artist with similar concerns will inform and re-energize my own work. As an arts writer, curator and Co-Director of Feminist Photography Network, I will also be considering ways to bring MacNeil’s work more into the public consciousness. Like many woman photographers, her contribution to the histories of photography is deeply underrepresented.